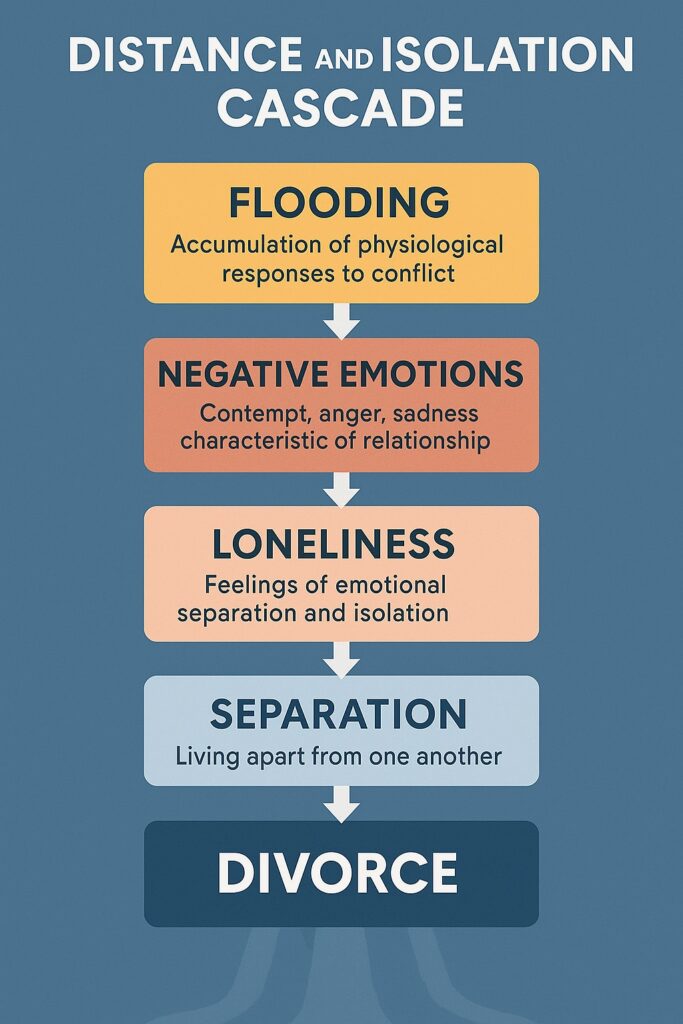

Introduction: The Cascade Concept

Marriages often break down in predictable ways. When we understand these patterns, it becomes easier for both therapists and couples to spot the warning signs early—and step in before things fall apart.

This article takes a deep dive into Dr. John Gottman’s “Distance and Isolation Cascade,” a research-based theory that explains how relationships gradually unravel. It looks at what causes the breakdown, how it affects people physically and emotionally, and which strategies can actually help turn things around. It also highlights how this process can look different for men and women and why timing matters when offering support.

In the messy world of relationships, few ideas are more important than the “Distance and Isolation Cascade.” Gottman came up with this term in 1993 to describe a chain reaction that often leads struggling couples toward separation and divorce.

Just like water tumbling down a waterfall, once the first problem starts, the rest often follow—fast and hard.

Gottman developed this theory after studying hundreds of couples over time. The problem? Not many of them divorced during the actual studies—maybe 2.5% to 5% per year. That wasn’t enough to study divorce directly. So instead, he looked for earlier warning signs—like doctors watching for chest pain as an early sign of heart trouble. What he found was a pattern of emotional disconnection that, once started, is hard to stop.

What makes this cascade especially important is how the steps build on each other, like rungs on a ladder. Gottman noticed that once a couple starts down this path, they tend to move through a predictable order: first, they feel less happy in the marriage, then they start thinking seriously about leaving, and eventually, they separate or divorce. Not every couple follows this exact pattern, but it’s the most common path that leads to a breakup.

Physiological Stress Response and Gender Differences in Marital Conflict

At the heart of this downward spiral is something called “flooding,” or Diffuse Physiological Arousal (DPA). It’s not just feeling upset—it’s a full-body stress reaction that happens during conflict. Your heart races, adrenaline kicks in, your thinking narrows, and suddenly, your partner feels more like an enemy than a teammate.

When flooded, individuals experience a range of physiological symptoms: elevated heart rate, adrenaline release, and perceptual narrowing (often called “tunnel vision”). In this state, partners begin to view each other as threats rather than allies, and their ability to access crucial relationship skills like empathy and humor becomes severely compromised. DPA is also a highly unpleasant and agitating subjective bodily state.

When you’re flooded, it’s incredibly hard to have a productive conversation. You can’t listen well, think clearly, or respond with empathy. Gottman jokes that people lose about 30 IQ points when they’re in this state. And he’s not wrong—your brain goes into survival mode.

Here’s where things get dangerous: when flooding happens often, couples start avoiding important conversations. They don’t bring things up because they know it won’t go well. Over time, that silence turns into emotional distance. And that’s the beginning of the cascade.

Flooding isn’t just emotional—it’s physical, too. To interrupt the cascade, couples need to learn how to spot it in themselves and each other, and how to calm down before trying to talk things through.

Men are especially vulnerable to flooding. They tend to get overwhelmed faster, stay flooded longer, and are more likely to shut down or withdraw. Research shows they often try to “keep the peace” by avoiding conflict—staying calm on the outside, even if they’re boiling inside (Raush et al., 1974). They might seem rational or detached, but really, they’re just trying not to explode.

The real danger of flooding lies in its cyclical nature. As episodes become more frequent, couples increasingly avoid discussing issues, believing that talking is futile. This avoidance marks the beginning of the cascade toward isolation, as partners start creating emotional and physical distance between themselves. Understanding and managing emotional flooding in couple relationships requires a multidimensional approach that integrates emotional awareness, regulation and communication skills, as well as attitudes of mutual openness and trust (García del Castillo-López, 2024).

The Five Key Measurements of Distance

Gottman’s research identified five crucial measurements that track the progression of the Distance and Isolation Cascade:

1. Loneliness Within Marriage

Perhaps the most poignant measurement is the experience of loneliness while married. This isn’t ordinary solitude, but rather the profound hurt of feeling emotionally isolated despite having a spouse physically present. When partners express sentiments like “Sometimes I feel so lonely it hurts,” it signals a dangerous disconnection within the relationship.

2. Parallel Lives Development

This measurement tracks how couples gradually arrange their lives to minimize interaction while sharing the same space. Like ships passing in the night, partners may maintain separate routines, activities, and social circles. This arrangement might seem peaceful on the surface, but it often masks deep relationship wounds and growing emotional distance. Couples who experience this don’t endorse items such as “We have a lot of fun together in our everyday lives.”

3. Problem Severity Perception

Using the Couple’s Problem Inventory, this measurement examines how seriously partners rate their marital issues. As the cascade progresses, couples tend to view their problems as increasingly severe and insurmountable. This shift in perception often reflects deeper changes in how partners view their relationship’s fundamental viability. Couples may endorse statements like: “My relationship can never succeed, and there is no more that I can do to keep the relationship going.”

4. Emotional Flooding Experiences

The frequency and intensity of flooding episodes serve as a crucial metric. These experiences, where partners feel overwhelmed by each other’s negative emotions, often trigger withdrawal behaviors that further fuel the cascade toward isolation. Endorsed items include: “Our discussions get too heated.”

5. Solo Problem-Solving Tendency

The final measurement examines partners’ inclination to handle problems independently rather than as a team. This preference for solving issues alone rather than collaboratively often indicates a breakdown in the couple’s ability to function as a unified unit. Couples will strongly agree to statements such as: “If I should have financial problems, my problems are totally my own. I cannot rely on my partner to help me out.”

These measurements are interconnected, each reinforcing the others in a complex web of relationship dynamics. The presence of multiple indicators often signals that a couple has entered the cascade toward dissolution, though early recognition of these patterns can create opportunities for intervention and repair.

The Health Impact of Marital Distress

The health consequences of marital distress and dissolution follow notably different pathways for men and women, revealing how gender differences influence the relationship between marital problems and physical wellbeing.

Women’s Health Response Pattern

Women’s health issues in troubled marriages typically stem from continued engagement with marital problems. They often assume increased responsibility for relationship repair while facing the dual stressors of hostile behavior and withdrawal (stonewalling) from their male partners. This may help to explain why women in abusive relationships tend to seek help to preserve their marriage rather than simply leaving it.

However, women generally maintain broader social connections during marital difficulties, preserving relationships with friends, family, and children. These social connections serve as crucial health buffers, partially mitigating the physical impact of marital distress.

Men’s Health Response Pattern

For men, the path to health problems follows a distinct sequence: emotional flooding leads to withdrawal, which often results in profound loneliness. This loneliness, rather than the marital conflict itself, becomes the primary driver of adverse health outcomes.

Men’s tendency toward complete withdrawal – not just from their female partners but also from children and social networks – can result in total social isolation. Their typically “leaner” social support systems outside marriage make them particularly vulnerable when marital problems lead to withdrawal.

Physiological Impact

Research by Kiecolt-Glaser and colleagues has demonstrated that marital quality directly affects immune system functioning. Lower marital quality correlates with suppressed immune response. This response worsens as the marriage does. Marital dissolution shows even stronger negative effects on immune functioning than mere marital unhappiness. These findings suggest that the cascade toward dissolution has measurable biological consequences, particularly affecting cellular immunity and stress response systems.

Contempt is not only the single best predictor of divorce, Gottman (2011) found that a husband’s expressions of contempt predicts the number of a wife’s infectious illnesses in the next 4 years. The frequency of contempt among happy couples? Nearly zero.

Transformation of Specific Complaints to Global Negativity

As couples progress through the Distance and Isolation Cascade, a profound transformation occurs in how they think about their relationship, their shared history, and each other.

From Specific to Global

Initially, couples’ complaints focus on specific incidents or behaviors. However, as the cascade progresses, these specific grievances transform into global negative perceptions (e.g. “You always…” or “You never…”). Partners begin to reinterpret their entire shared history through an increasingly negative lens, affecting their view of:

- The fundamental nature of their relationship

- Their shared values and beliefs

- The meaning and worth of their marriage

- Their partner’s basic character

Impact of Prolonged Negative Emotional States

Gottman’s research reveals that extended periods in negative emotional states (what he terms “Q = -1”) lead to escalating negative interpretations. Partners, especially husbands, begin to express increasing disappointment with the marriage and lose their sense of fondness for their spouse. The shared vision of marriage that once united them erodes, replaced by individual narratives that often conflict with each other.

Deterioration of Shared Memories and Relationship Perception

A particularly significant aspect of this transformation is how it affects memory. Partners begin to:

- View their shared history differently from each other

- Lose access to positive memories while negative ones become more prominent (The Zeigarnik Effect)

- See conflict as increasingly pointless

- View their lives as chaotic and out of control

- Perceive themselves as fundamentally separate rather than united

Predictive Factors and Warning Signs

Through extensive research, Gottman has identified several reliable predictors of marital dissolution that emerge well before actual separation occurs.

Early Indicators

The presence of what Gottman terms “The Four Horsemen of the Apocalypse” – criticism, contempt, defensiveness, and stonewalling – serves as a powerful predictor of marital problems. Contempt, particularly when expressed by wives, emerges as the single strongest predictor of dissolution across studies. It signals the breakdown of affection and empathy within the marriage, with admiration serving as its natural antidote.

Physiological Markers

Skin conductance measurements and other physiological indicators during conflict discussions provide objective evidence of emotional flooding. Men’s greater physiological reactivity during marital conflicts helps explain their increased tendency toward stonewalling, as they attempt to protect themselves from overwhelming physiological arousal.

Behavioral Patterns

Key behavioral predictors include:

- Increased hostile-detached patterns during conflict

- Decreased repair attempts during arguments

- Rising emotional disengagement

- Growing preference for parallel rather than shared activities

- Surprising emergence of sadness as an early predictor of dissolution

Self-Report Reliability

Gottman’s research reveals that couples’ own assessments of their marriage’s problems often prove remarkably accurate. The Weiss Marital Status Inventory (Weiss & Cerreto, 1980) shows that a significant proportion of intact marriages already contain indicators of future dissolution, with serious considerations of separation serving as particularly reliable predictors of eventual divorce.

Breaking the Cascade: Intervention Strategies and Timing

Understanding the Distance and Isolation Cascade provides crucial insights into how and when to intervene in troubled marriages. The key to successful intervention lies in recognizing that certain approaches become more or less effective depending on where couples are in the cascade process.

Emotional Regulation and Self-Soothing Techniques

Emotional soothing emerges as a fundamental skill for breaking the cascade, particularly in its early stages (Gottman, 2016). Partners must learn to:

- Recognize signs of flooding in themselves and each other

- Develop personalized soothing techniques

- Practice these skills while in a physiologically aroused state

- Take strategic breaks during conflicts to allow for physical and emotional calming

Importantly, this soothing process cannot be effectively managed by a therapist alone – couples must develop these skills themselves and learn to implement them autonomously.

Developing Pattern Recognition and Emotional Self-Awareness

Breaking the cascade requires partners to develop heightened awareness of their own patterns (García del Castillo-López, 2024). This includes:

- Understanding their typical responses to relationship stress

- Recognizing their individual flooding triggers

- Acknowledging their role in maintaining negative patterns

- Identifying when they’re entering the parallel lives phase

The development of this self-awareness proves particularly crucial for men, who must learn to recognize their greater susceptibility to flooding and its impact on their tendency to withdraw.

Evidence-Based Strategies for Relationship Repair

Effective intervention typically involves several key components:

- Learning to validate each other’s emotional experiences

- Improving trust and trustworthiness (Gottman, 2011)

- Developing admiration practices to counter contempt

- Creating new shared meaning and rituals of connection

- Rebuilding friendship and fondness through intentional attention

- Establishing effective repair mechanisms for when conflicts arise

These steps must be implemented systematically, with attention to each partner’s capacity for engagement at different stages of the cascade.

Optimal Timing for Therapeutic Intervention

Gottman’s research emphasizes that timing plays a crucial role in the success of interventions. Early intervention, before couples have developed entrenched negative patterns and while they still maintain some positive sentiment override, offers the best chance for success. Positive sentiment override happens when nondistressed couples discount negativity and emphasize positivity in their partners (rose-colored glasses) vs. a negative sentiment override model (Weiss, 1980), in which distressed couples discount positivity and emphasize negativity in their partners.

However, this creates a paradox: couples are often least likely to seek help when intervention would be most effective.

Role of Mutual Commitment in Relationship Recovery

A critical insight from Gottman’s work is the role of commitment in breaking the cascade. Using an analogy to Alice in Wonderland, he describes true commitment as jumping into the relationship “with both feet,” fully engaging in the journey regardless of its challenges. Successful intervention requires both partners to recommit to this level of engagement, deciding that their relationship is where they will get their needs met.

Maintaining Relationship Progress and Preventing Relapse

For couples who successfully break the cascade, several factors emerge as crucial for maintaining their progress:

- Regular practice of soothing techniques

- Continued attention to building positive interactions

- Maintenance of shared activities and experiences

- Ongoing monitoring of distance indicators

- Regular relationship check-ins and maintenance discussions

The process of breaking the cascade isn’t simply about stopping negative patterns – it requires actively building new, positive patterns of interaction while maintaining vigilance against returning to old habits.

Closing

Understanding the Distance and Isolation Cascade represents a crucial step forward in both marital research and clinical practice. While the path toward marital dissolution often follows predictable patterns, this knowledge provides opportunities for early identification and intervention. The complex interplay of physiological responses, behavioral patterns, and cognitive transformations in troubled marriages suggests that successful intervention requires a multi-faceted approach, considering both timing and individual differences. As research continues to evolve, these insights offer hope for couples willing to engage in the work of relationship repair, while providing clinicians with evidence-based frameworks for guiding couples through the challenging process of rebuilding connection.

References

Booth, A., & White, L. (1980). Thinking about divorce. Journal of Marriage and the Family, 42, 605–616.

Cummings, E. M., & Davies, P. (1994). Children and marital conflict: The impact of family dispute resolution. New York: Guilford.

García del Castillo-López, Á., Berenguer-Soler, M., Pineda, D. & García del Castillo, J. (2024). Emotional Flooding in Couple Relationships: Psychosocial Aspects and Regulatory Strategies. 10.5772/intechopen.1006183.

Gottman, J. M. (2016). The Man’s Guide to Women: Scientifically Proven Secrets from the Love Lab About What Women Really Want. New York: Rodale Books.

Gottman, J. M., Katz, Lynn Fainsilber. L. & Carole, H. (2013). Meta-Emotion: How Families Communicate Emotionally. London: Routledge.

Gottman, J. M. (2011). The Science of Trust: Emotional Attunement for Couples. NY: WW Norton.

Gottman, J. M. (1993). What Predicts Divorce?: The Relationship Between Marital Processes and Marital Outcomes. Psychology Press: location Hove, East Sussex, United Kingdom.

Glaser, R. (1988). Marital discord and immunity in males. Psychosomatic Medicine, 50, 213–229.

Kiecolt-Glaser, J. K., Fisher, B. S., Ogrocki, P., Stout, J. C., Speicher, C. E., & Glaser, R. (1987). Marital quality, marital disruption, and immune function. Psychosomatic Medicine, 49, 13–33.

Kiecolt-Glaser, J. K., Kennedy, S., Malkoff, S., Fisher, L., Speicher, C. E., & Glaser, R. (1988). Marital discord and immunity in males. Psychosomatic Medicine, 50, 213–229.

Notarius, C., & Markman, H. (1994). We can work it out. New York: Putnam.

Raush, H. L., Barry, W. A., Hertel, R. K., & Swain, M. A. (1974) Communication, conflict, and marriage. San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass.

Weiss, R. L., & Cerreto, M. C. (1980). The Marital Status Inventory: Development of a measure of dissolution potential. American Journal of Family Therapy, 8(2), 80–85. https://doi.org/10.1080/01926188008250358

Wilson, B. J., & Gottman, J. M. (1995). Marital interaction and parenting. In M. H. Bomstein (Ed.), Handbook of parenting, Vol. 4: Applied and practical parenting (pp. 33–56). Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates.